Spirit and Communication

We are in Charboneau les Bains au Lyon, in the Rhone Valley, the “gastronomic capital” of France, exploring the ancient city, its countryside and sampling the differences between Parisian and Lyonese cuisine. It is a welcome rest from the hassle-hustle of the business life from which I soon retire and the quietude of this rural hotel helps healing. We sleep in. The beds are cool and soft and there is no stop watch clicking for anything. This is a luxury, I know.

The time zone difference between Seattle and France has presented a more difficult adjustment than in the past and I realize that if I am to be here as I plan to be to write in the future, perhaps stay for at least three months in a Paris Left-Bank flat or a Bourdeaux or Provence cottage, I will need to spend at least two weeks acclimating and spend enough time in the future learning the French and Italian languages. I grew up in a second generation Italian-American family but assimilation was more important than preservation of the “Old Country” traditions and language unfortunately. It is fortuitous, however, that five years of classical training in Latin and Greek has helped me in many circumstances.

Last evening, after a day of resting and writing (finally re-starting Isthmus), we drove with Dame Edith, our GPS machine guide with a British accent, to a trendy bistro in Tassin la Demi Lune where we had a typical meal…which surpasses anything I have found in the US at comparably priced bistros. We were intrigued by the interaction between our waiter, who spoke very little English with the two of us who speak very little French. Unlike previous episodes during high season exchanges in Paris, where the waiters and shopkeepers are besieged by diverse, demanding tourists, this “discussion” was gentle and playful. We drew pictures and went back and forth with something special that resulted in a kind and effortless evening. Mime is useful as well.

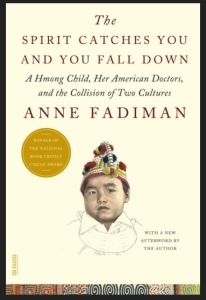

Afterwards, I thought about the book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman, an intense, beautifully written story about the interaction of Hmong people, translocated to the central California region during and after the Viet Nam war, with the public healthcare system in that area. The miscommunication that occurs between the care seekers and care providers, the tragic failures that result when exhausted health care providers lose all ability to empathize or learn about cultural differences, is symptomatic of the problems that result from every cultural intersection. It is, of course, much worse when the prevalent attitude of one culture is based on an assumption of its superiority over another, as was the case in the foundational story for Widow Walk.

I have used Fadiman’s excellent book in my lectures about “bedside manner” to our medical directors and to Emergency Medicine residents at Cornell-Columbia, UW, UCLA and U Chicago. I have also referred to the book in risk management lectures, because we have observed that patients and their families can forgive a bad outcome as long as the care-givers are perceived as caring and have communicated well. If they care enough to learn a language, use effective translators, take the time to be certain that the patient is given the opportunity to understand the risks and probabilities of diagnosis and treatment, the chances for efficacious outcomes are invariably enhanced. It is a major failure in health care provider education that the development of interpersonal skills is so often given short-shrift.

We return to Paris for three more days before embarking home to Seattle.