A Hunting Story

On a recent hunting journey, I had the good fortune of being able to take a rifle shot at a magnificent elk from 1,000 yards. It was a moment where everything came together like the gears of an invisible clock — all the planning, the thinking, the training, and the movements. It was indeed an epic hunt — and one whose lessons I am still learning. In this month’s blog, I invite you into the story of that hunt and the 1,000 yard shot.

Different Universes: 1008 yards apart

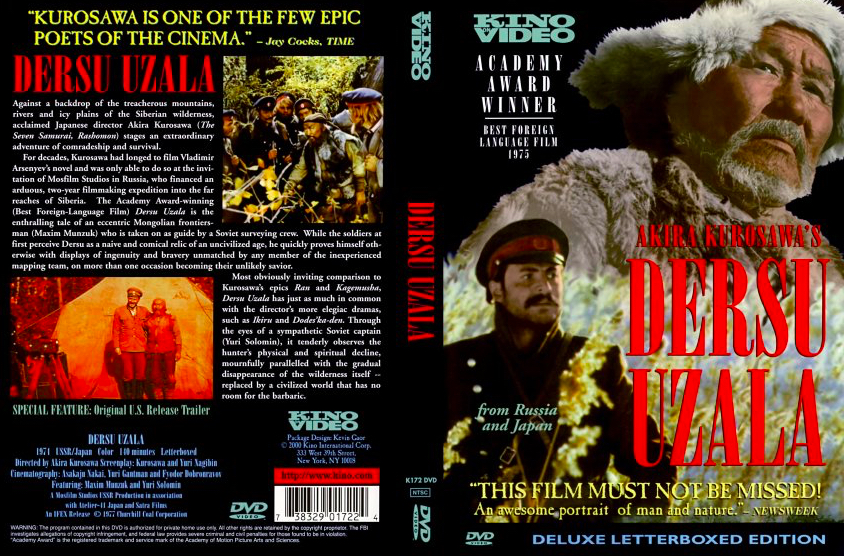

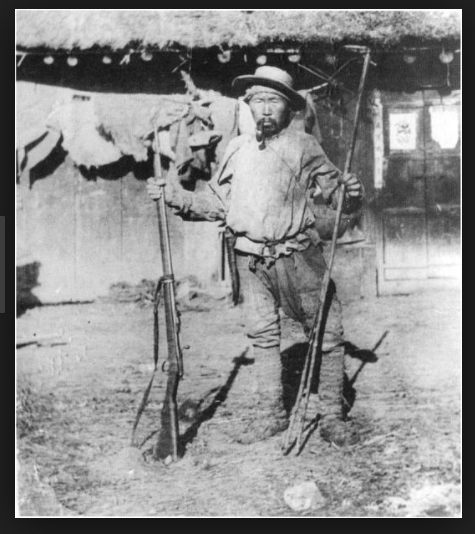

When I think of hunting, I often recall a definitive scene from the Japanese-Russian masterpiece by Akira Kurosawa, Dersu Uzala (1975) in which the protagonist, an aging hunter, Dersu, fails to see a Siberian tiger that is stalking him and the party he is guiding. It is at that moment that he realizes his old eyes have failed him. His life, as he knows it, is now over. He can no longer be a hunter or a protector. He has become prey himself.

The film said much about the arc of life, in an atypical setting — my favorite type of storytelling. It also meant a lot to me because, yes, I also am a hunter. Have been since my father took me with him on an Eastern Washington hunt when I was a small boy. Very much a transformational coming-of-age experience for a seven year old, I realize.

The hunt, and all of its symbolism, defined much of me from that point on. It coincided with many other things that were part of my formative years. I grew up with rifles, pistols, bows and arrows, and as a boy I watched on TV and in the theater hand-held weapons being used in Winning-the-West Westerns. I saw them depicted as defensive “equalizers” to protect and defend.

My father grew up a hunter as well and often spoke with words that came from that vocabulary. Because he respected the power and understood the hazards of these tools, he made certain I was trained in rifle and pistol safety classes. I learned to shoot a bow well enough that I could hunt elk and deer with it. We walked the woods and learned the signs of the animals we tracked. Over the years, our family enjoyed the game meat at the table, cooked with the Porcini, Chantrelle and Morels we collected while foraging in the forest, and traded stories about the hunting expeditions with other family members. It was family lore. We seldom ate beef, especially “steak” because it was so expensive. And it didn’t taste as good, frankly.

I really never questioned the logic of preferring game meat to beef, pork or chicken. I saw a slaughter house when I was a young boy and from that experience learned to compare the ethics of providing for meat for the table from a hunt versus the “humane” methods that the commercial meat industry says it employs. Although I disagree with it, I understand the perspective of the vegetarian and detest cruelty.

I believe one should respect hunting for its original purpose. Thus, I do not hunt for trophy racks or hides, nor do I compete for the size of the antlers, but I do use the antlers to make jewelry and wood-turning sculptural adornments. I will only hunt for game that I can bring to the supper table. I made the mistake of posing for a picture with my first elk harvest several years ago, and regret that.

Ortega y Gasset said in his Meditations on Hunting: “One does not hunt in order to kill; on the contrary, one kills in order to have hunted…If one were to present the sportsman with the death of the animal as a gift he would refuse it. What he is after is having to win it, to conquer the surly brute through his own effort and skill with all the extras that this carries with it: the immersion in the countryside, the healthfulness of the exercise, the distraction from his job.”

I agree. The drama of the hunt – the painstaking process of finding markings and tree rubbings, listening for the nuances of wild animal sounds, waiting patiently for hours in the cold, calling in a raging bugling elk in the rut, holding an absolute, still silence in a moose hunt, competing with wolves, coyotes, cougars and grizzly bears for prey, traipsing for miles on diverse, uneven terrains and waiting for the rare moment to take a shot – has always fascinated me. It is satisfying and it is clean.

Of late, I have spent a great deal of time in the forests and plains of North America hunting for game animals that will replenish our home stores. In the past year, I participated in four long, arduous hunts — in Calgary, Kamloops, New Mexico and Colorado. Despite an enormous amount of effort, I achieved “success” (i.e., bringing home a “harvested” animal) on none of those efforts.

Over time, in addition to learning about short-range bow hunting, because it is difficult to get close enough to an elk after the rutting season is over, I also have taught myself to understand the science and art of long-range rifle marksmanship, which means I need to have a good understanding of ballistics, with all of the variables that impact accuracy. It is much more difficult to hit a 5″ target at 200 yards than it is at half that distance. Because of the multiple variables that must be taken into account – the muzzle velocity of the load, the weight, aerodynamics and “ballistic co-efficient” of the projectile, the wind speed and direction at the muzzle and at the point of impact, the altitude, humidity, temperature and barometric pressure, and the size and movement speed of the target – hitting a target at 1000 yards is an enormous challenge. And you have to do it “ethically.” If you hunt for food, you must be certain that you do not simply wound an animal. You have to take it down, one way or another, with a precise shot, which increases the difficulty.

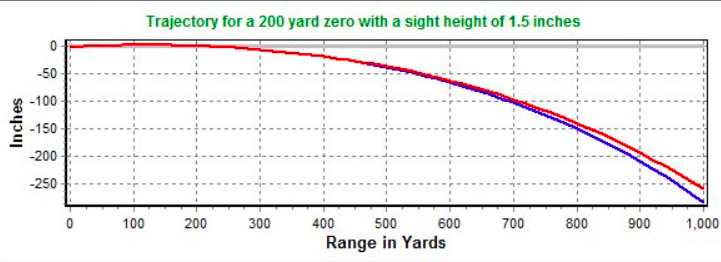

Bullet flight path with measured drop (no wind) for .338 Lapua rifle

On my last hunt of this season, after several days of seeing no game, I glassed a bull elk grazing in front of the forest it had exited in the late afternoon. Because we were on a high bluff, there was no way to stalk it and get closer. The ranging meter indicated we were 1008 yards away. The light was fading quickly. It was now or never. Fortunately, I had spent hours practicing for a moment like this. So, after saying a little prayer to the elk-god and Artemis, I took the shot.

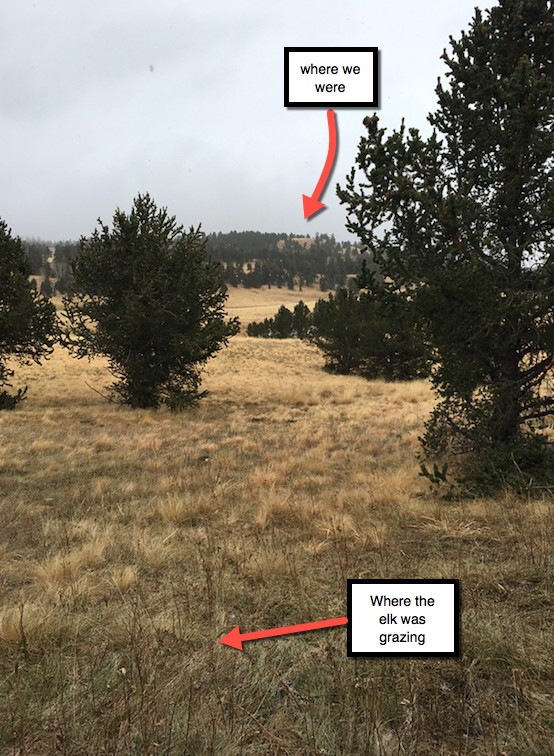

Below is a video of the ridge where we sat: – 9500 feet elevation, 34 degrees F, falling barometer at 29.2, cross-wind velocity at 10-15 mph. My hunting companion was as cold as I was.

The rifle I used was a .338 Lapua Magnum 10:1 twist, 28″ carbon-fiber barrel, manufactured by Christianson Arms in Utah. I shot a 280 grain Barnes bullet with a ballistic co-efficient of .661 (G7), and a muzzle velocity of 2950 fps. The scope is a Nightforce 5-25×56. The bullet drop at 1008 yards for this custom load is 252 inches and I calculated that the cross-wind velocity would push the bullet @ 8 feet laterally by the time it reached its target. As you can see from the video, from the ridge where we were sitting we were shooting down at a 30 degree angle.

A lucky, albeit well-practiced, 1000 yard shot, it was. My friend, glassing through his spotting scope, said it was a “brisket hit” – fatal but unfortunately, not immediately — so we would have to track it, possibly for a long time. Thus we waited a long time to commence, lest we “jump” the animal where it went to rest, and thus provoke flight deeper into the woods where we might never find it. Ever.

After a half-hour of waiting, we walked to the place in the picture below, found blood at the spot of impact and then tracked our elk into the periphery of the woods. We continued searching well into the evening. Unfortunately, when we moved into the thicker underbrush, my friend did indeed spook the animal, and it ran away into the densest part of the extensive woods. In the darkness, we couldn’t see anything, so we returned to camp, borrowed an infrared camera from a friend and came back after midnight to see where the elk was hiding. But once they die, their heat signature fades away. I didn’t want the animal to be alive and suffering, so I half-hoped the infrared wouldn’t help us. It didn’t. No heat signature. The elk was down, hidden in the darkness and the tree-fall.

infrared signature of an elk deep in the woods at night

No pictures of the harvest – we never found the elk. Wounded elk hide themselves from predators very well in a woods filled with downed trees. Their antlers look like branches, and tree trunks and fallen limbs obscure everything. After hours of searching, I did find several skulls and bones of three other elk — the cleaned, chalk-white remains of older animals that almost certainly had been mortally wounded during a fight with a competitor or had been downed fatally by another predator — a wolf, mountain lion or another unlucky hunter like myself. There was no waste. Their remains had been picked apart by scavenger animals —coyotes and birds.

At the top of this page is the view from the ridge and another from the place where the elk stood.

So, after four hunts and 40 days of traipsing, I had gotten only one shot and am left with no game meat to season or cure. This holiday we will not serve elk roast, or well-preserved coppa or braciola. Our holiday treat will be Dungeness crab with angel-hair pasta.

I know it is an ego-driven challenge, that long distance shooting. I have thought about the ethics of the situation I described, and am pondering whether, in the future, I should avoid taking long shots on big game, harvestable animals unless I can be absolutely certain I will take it down immediately, thereby avoiding a similar experience. I am a carnivore, but don’t want the animal to suffer with a prolonged death. (“Ethical” in the beef-meat industry, by the way, is conveniently defined by the means with which they kill their product — a brain shot from a piston-driven bolt while the cattle is confined in a slaughter pen).

I consider myself a very good marksman and can consistently hit a stationery 10″ target at 1000 yards, but perhaps I am not a good enough marksman. Perhaps I need to practice even more.

In any case, eventually, I will no longer be able to hunt — my bones will mightily protest the trek, or my eyes will fail as did Dersu’s.

Should I give up hunting now, just become a vegan, or buy beef from the supermarket and save my long distance marksmanship for paper targets – thereby conveniently using arguments about the ethics of it all to preempt one of the many humiliations that come with aging?

Unlikely that I will do that. I like game meat on my table too much and I understand that the deliberate experience of acquiring it is part of me.

And like Dersu, I will hunt as long as I can.

Each Christmas we are the recipients of canned, wild caught salmon and elk “burger” and or home made sausage from my son’s father in law who lives in Idaho. He hunts pheasant, elk, deer and others. He also fishes extensively. He “cures” quite a bi of what he brings home too. It is something that we look forward to with great joy.

I guess I’ll have to watch Dersu Uzala (1975) and see how can I relate to it. Thanks for the post.