Artist’s Chat with Shannon Polson: Representing the Wilderness Experience in Literature

In this Artist’s Chat, I am excited to talk with Shannon Polson, someone who is not only a fantastic writer, but an inspiring individual who teaches us all what is possible when we commit ourselves to pushing our own limits and cultivating excellence. Shannon is both a best-selling author and one of the first women ever to fly the Apache helicopter. As if those facts weren’t recommendation enough, I can also say that she is a wonderful storyteller and a great person to just chat with.

Last year I had the chance to sit down with Shannon and talk about things like:

- Why wilderness and adventure have that magical draw on our souls

- How we each, as authors, connect with stories that live in the landscapes around us

and, - What it takes to represent the vastness and mystery of the outdoors in words on the page

It was a powerful conversation that is on my mind this month as I dive head-first into research and development for Book IV of the Widow Walk Saga.

These are a few of my favorite gems from Shanon, but really the whole interview is fantastic.

“In many ways wilderness is a foil for the human experience in its purest form. It allows all those extremes of adventure, fear, hope, terror, joy, exaltation, unadulterated by any kind of human interaction. There’s a real opportunity there.”

“I think music and wilderness do something similar in that they connect us to these higher places. These pure unadulterated places in ourselves.”

“Hunters frequently have some of the closest relationships with the land. An appreciation for what it offers, what it brings, what it sustains, how it sustains, and how to have a respect for that whole process. It’s very much part of all the indigenous cultures, as it has to be, and so I’m an aspiring hunter, believe it or not.”

“I always ask the women I profile, how they would define grit. I get lots of different definitions. I came up with a definition early on, that it was a dogged determination in the face of difficult circumstances. Which is not very lyrical, but I think, in a way, it’s appropriate, because it’s not lyrical.”

I invite you to join us and learn more. Click here to listen:

Representing the Wilderness Experience in Literature, Part 1

Representing the Wilderness Experience in Literature, Part 2

Representing the Wilderness Experience in Literature, Part 3

Artist Chat guest: Shannon Polson

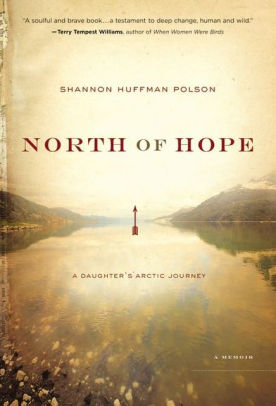

Shannon Huffman Polson writes about the borders we navigate every day. Her first book, a memoir called North of Hope, was released spring 2013 by Zondervan/Harper Collins. A short book of essays, The Way the Wild gets Inside, was released in December 2015. Her essays and articles have won recognition including honorable mention in the 2015 VanderMey Nonfiction Prize, and appear in River Teeth Journal, Ruminate Journal, Huffington Post, High Country News, Seattle and Alaska Magazines, as well as other literary magazines and periodicals. Her work is anthologized in “The Road Ahead,” “More Than 85 Broads” and “Be There Now: Travel Stories From Around the World.”

Shannon Huffman Polson writes about the borders we navigate every day. Her first book, a memoir called North of Hope, was released spring 2013 by Zondervan/Harper Collins. A short book of essays, The Way the Wild gets Inside, was released in December 2015. Her essays and articles have won recognition including honorable mention in the 2015 VanderMey Nonfiction Prize, and appear in River Teeth Journal, Ruminate Journal, Huffington Post, High Country News, Seattle and Alaska Magazines, as well as other literary magazines and periodicals. Her work is anthologized in “The Road Ahead,” “More Than 85 Broads” and “Be There Now: Travel Stories From Around the World.”

After a childhood in Alaska, Polson was commissioned as a 2LT in Army Aviation and became one of the first women to fly Apache helicopters, serving on three continents and leading two flight platoons and a line company. In 2009 Polson was awarded the Trailblazer Woman of Valor award by Senator Maria Cantwell. More at ShannonPolson.com.

* * * EDITED TRANSCRIPT BELOW * * *

Conversations edited for clarity.

Please listen to the recordings to catch all the laughter!

Part 1: Wilderness as a Foil, Shannon’s book North of Hope, and Approaching Wilderness as a Setting

Scott James, Interviewer: Our topic today is on representing the wilderness experience in literature, and what comes out of that. I’ll start by saying that you’ve both written several books that utilize remote and vast wilderness settings. They play key parts in your narratives and I’m curious just to hear a little bit about why you decided to set one or more of your books in those areas. Shannon, maybe we can hear from you first.

Wilderness as a Foil for the Human Experience

Shannon: In many ways wilderness is a foil for the human experience in its purest form. It allows the human experience to be almost as pure and unadulterated as it can be, with all those extremes of adventure, fear, hope, terror, joy, exaltation. It’s unadulterated by any kind of human interaction. So, I think, there’s a real opportunity there.

North of Hope was set in arctic Alaska, in the northeast corner because that’s where the incident that provoked the narrative took place. I think it then became, not just a backdrop, not just something that allowed those human experiences to unfold in their purest form, it became an actor in the story. It was something that became an integral part of the story, which it didn’t have to be of course.

If you allow it to be and if you have that relationship, or allow yourself that relationship, then it can be a very active player. I think in North of Hope and in the essays in The Way the Wild Gets Inside, it’s always the case.

North of Hope

Scott: Would you tell us a little about North of Hope? It might be everybody’s first time hearing about it.

Scott: Would you tell us a little about North of Hope? It might be everybody’s first time hearing about it.

Shannon: North of Hope is a memoir about a trip I took in northeast Alaska. It follows a trip my father and stepmother had taken in 2005. They were rafting the Hulahula River over their 16th wedding anniversary and they were killed by a grizzly bear.

North of Hope takes their trip and then parallels it with the trip I took the year after. it weaves those two stories together, as well as memories of growing up in Alaska. You can see, given the circumstances of the narrative itself, the wilderness was already an active player. I certainly had to permit it to continue to teach, instruct, and warn. To do all of those things that it can do.

Scott: That sounds very powerful to have written and a very powerful journey to have taken in the steps of that kind of incident.

Shannon: I think the other opportunity was the development of a relationship with this part of a state. Although I had grown up in the state of Alaska, I had never been to this far northeastern corner. It’s very remote and very difficult to get to. It took two flights just to get to the place where the trip began. Those are small, bumpy planes on dirt airstrips and actually no airstrips at all in some cases.

It allowed me not just to learn from that place, but to really grow in this respect that then turned into a real love and appreciation for this wilderness landscape. I think that ends up playing into all kinds of current issues today, but certainly the development of the narrator, which in a memoir of course is the author. But in the narrator’s development, or in my development, the wilderness played and continues to play a very big part.

Scott: You answered the question I was going to ask, which is, how did that incident and then the trip you then took, affect your relationship to the wilderness?

Shannon: Well I would say the only thing I would follow up with is a sense of responsibility to this place. That was the piece I’ve left out. The experience that really formed intensely after that trip was that I had a sense of responsibility to this place that had taught and continued to teach me so much. While it was so powerful it was also sometimes terrifying, sometimes beautiful, sometimes tragic, it was also quite fragile. There was also a real threat and there continues to be a real threat of destruction to this place because of things we might do carelessly. There was a sense of responsibility that grew strongly after that opportunity to spend time and interact with it in that way.

Gar: Shannon, could you talk about North of Hope as it relates to your music. Because Scott didn’t mention that you are also a singer as well, and you sing classical works. A “colloquium.” Is the right term?

Shannon: Yes, Seattle Pro Music Guide, who I have been with for many years. Yes.

Gar: Could you elaborate a little bit, as it relates to North of Hope? I think I recall hearing the concept about a relationship to Mozart’s Requiem here. Could you talk about that a little bit?

Shannon: Yeah, absolutely. I tried to fit a lot into it. I think we all do as authors. And the key really is to pare back to the essentials. I realized the essentials had to be in here.

There are three of them. One was wilderness; one was faith; and one was music.

In the year between the two trips that are braided together in this narrative, I had the opportunity to sing with Seattle Pro Musica. We sang the Mozart Requiem under the direction of Itzhak Perlman, which was stunning, just an unbelievable experience. Of course, the Mozart Requiem in the Christian tradition is a mass for the dead, right? It is something that is both a lament and an exaltation. It’s this combination of all the extremes of emotions we feel during grief. And yet, this connection to something much bigger.

In many ways, I think music and wilderness do something similar in that they connect us to these higher places. These pure unadulterated places in ourselves.

The way I tried to work with it initially was to put this singing of the Mozart Requiem and that experience up front in the book. There was more of a chronological timeline but that ended up being a little chunky because it didn’t really come back. I would try to artificially connect back to it later on and it just didn’t seem to work very well. It just seemed out of place in the beginning.

So instead what I did was – and this was borrow from Kathleen Norris’s Dakota, where she takes her weather reports and intersperses them throughout the narrative – was take the Requiem and intersperse them in very short sections throughout the narrative to connect the river and the Requiem, which is this sense of movement. I really wanted to have the title reflect this, but it was not agreed upon, so. There’s this sense then of connection between the river and the Requiem, and the journey of the narrator going through her internal journey and the external journey being very much connected to this requiem. The movement of the requiem meant of course from lament into faith.

But the second part of that, Gar – which is my really nerdy part that I only answer in these sorts of conversations – is the Mozart Requiem was the last piece of music that Mozart wrote. And he never had a chance to finish it because he died in the middle of its composition.

The movie that’s been made of it [Amadeus] has a lot of Hollywood around it. But at the end of the day his widow really needed the money from the commission. So, she asked his colleague, whose name was Sussmayer, to finish it.

There’s been lots of study done on which parts of the Requiem are Mozart’s and which parts were finished by Sussmayer. I connected that concept of finishing the trip that my father and stepmother were unable to finish, with this finishing of the Requiem. The pieces referenced, or the movements of the Requiem that are referenced, in the first part of North of Hope are all those movements Mozart completed himself. Then the movement referenced after arriving at the beach where they’d been killed by the bear, is one that Sussmayer had to finish.

I tried to make those connections in small ways, which is the sort of fun internal stuff authors do that other folks may or may not notice or connect to. But I really did feel that connection of the river to the Requiem, of finishing work that has been left unfinished, which is something I think we can all relate to in our lives. Something we might all hope would be done for us, is something I wanted to have part in. And someone who’s very familiar with Mozart will understand that piece of the Requiem.

Wilderness as Setting

Scott: Gar, speaking of the wilderness becoming a character and growing out of personal experience, can you speak to that? Are you currently in a setting used in your book? Is that true, or not quite?

Gar: Well, the first two books have a strong backdrop of extreme environments. In the first book, Widow Walk the protagonist moves up north with hope of finding her kidnapped son and experiences what one would expect in the remote areas of British Columbia, not too far away from where you were, Shannon. The heroine has to confront a grizzly bear in the process of her exploration, and survives the overall extremes.

The second book, Isthmus, takes place in Panama where it’s just the opposite. The average temperature when the protagonist would have crossed the isthmus would have been in the mid-90’s, extremely humid, and in torrential downpours. I walked the beaches, looked at the old caves, traipsed through the jungles there and tried to see the remnants of the old Spanish Camino Real, which is completely overgrown of course; there’s very little of it left. And from those explorations, got a real sense of the power of nature from that standpoint.

In comparison to Shannon, however, I’m probably more fearful of the environment. I mean, I am an armchair traveler in many respects. Although I am a hunter, and I will be going up north to do some moose hunting, elk, and caribou this fall, I consider myself an ethical hunter. I don’t do it for the pleasure of killing or anything like that. I only will only hunt what I think I can harvest and then share with my family.

Coming into nature that way, whether it be with a rifle or with a bow, gives me a good feeling of the relationship we have, the signs and signals the lands gives us as we are moving through it…. However, I will never go hunting in Panama. One is more likely to be the one hunted down there.

Shannon: Are you going up to Alaska, Gar?

Gar: To the Northwest Territory.

Shannon: Oh fantastic.

Gar: I haven’t studied the maps at this point. To know exactly where. I think we’re going into Yellowknife, we’re flying there and then moving north. I’m not sure whether we’re going to be on horseback or not.

Shannon: Oh wow. Fantastic.

Gar: Yeah, it’s fun. So, that’s my relationship to it. I have immense respect for people who’ve grown up and know it and celebrate it the way that Shannon has.

Shannon: I just wanted to say, I think hunters frequently have some of the closest relationships with the land. An appreciation for what it offers, what it brings, what it sustains, how it sustains, and how to have a respect for that whole process. It’s very much part of all the indigenous cultures, as it has to be, and so I’m an aspiring hunter, believe it or not. And I have two little boys, so I figure I’d better get on it!

Gar: I will tell you, your description of the event about your father and your stepmother, was chilling. I tried to do the same thing in one chapter related to that, where Emmy meets Ursa, so to speak, a rogue, old grizzly bear that has one eye. And I wrote that chapter long before I met you, but it was kept alive by what I read in your book. I will tell you that one of the deterrents to me ever in the past going up north and hunting has been dealing with bears; they scare the hell out of me. And my encounters with them while hiking a couple of times were not pleasant, so I appreciate it from that standpoint.

Shannon: They’re worthy of respect.

Part 2: Wilderness as a Character, an Author’s Role in Representing the Wilderness, and the Author as a Leader

Bringing the Wilderness Alive as a Character

Scott: Is there a certain way you think about it, or a technique you use in the writing, to convey what it is about the wilderness or bring it alive as a character?

Gar: I don’t like the extremes, but if I were to die in the wilderness, I would prefer it to die in the cold.

Scott: Okay! We will call you on that.

Gar: Because you numb up and then you just go to sleep. And you lose your relationship to your arms and your legs and your periphery first, and then eventually you go out, and we all read of course To Build a Fire and those short stories by Jack London from way back when.

But on the other hand, in contrast to extreme cold, my neurons stop working when it gets hot. And it’s like they all shut off; they have tripped levers as the temperature goes up. My experience traveling through Panama convinced me that I don’t know how people exist within that extreme environment. And so, for me to able to write about it, I spend a lot of time traveling through Panama, going into the jungle, getting on the bungo boats, walking on the beaches where the events were eventually going to occur. I hadn’t written it yet but I had this vision.

And there was a term that a friend of mine used, who’s a master landscape architect. He said, “Nature has an overwhelming indifference to us as human beings.”

We tend to think of ourselves as the center of the universe, and yet, effectively, nature gives us a comeuppance. To be able to write about it, I think you have to immerse yourself in it, and retain the memories of it, and you have to try to create the descriptions of what it’s like… to accurately depict it.

For me at least, I have to experience the pain and suffering of the process itself. If I’m going to put a human being in that backdrop, and test that human being with what the environment gives to them. Does that make sense?

Shannon: Absolutely.

Scott: That makes sense to me. How about you, Shannon. How much does that overlap with your process?

Shannon: I agree completely with Gar.

I think one of things I realized as a writer that I needed to do, was really explicate this relationship I feel is integral to my growing up. It’s one thing to say that I grew up in Alaska and I love Alaska, but it’s another thing to really, to explicate it so that the reader can understand it’s place, especially the Arctic, that most folks, even in Alaska, have never traveled.

As I was writing North of Hope, I kept a detailed journal on the trip itself, so I certainly referred back to that. I also – to make sure that memories and my journals were accurate – would cross-reference against, the Naturalist’s Book of the Arctic, which I would go back to and check for additional information.

Then I did a second trip before I published North of Hope, while I was pregnant with my first son. My husband and I took a trip; he had never been to the Arctic, and I really wanted him to experience this place that was so important to me. We didn’t do the same trip I did, but we did do a 14-day hiking trip over in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. We followed a porcupine caribou herd, which was just an incredible experience by itself. In that same landscape – really in that same area – a few drainages over from where I had been in the story that became North of Hope.

Our second trip was in the Western Arctic, which is a slightly different. There’s more open landscape. By that point I was involved with helping to protect it through the Alaska Wilderness League and working on their board. I wanted to understand that place when I was talking to people about it.

Both certainly informed the experience. We did have one bear encounter in the Western Arctic, which was a standard one. It came down the hill towards us and we came up towards it then we stopped, waved our hands, yelled, and it ran off – that’s typically what happens. We certainly took precautions in some regards prior to my father and stepmother dying might have seemed excessive, and in bear country we always sleep with an electric fence and we carry firearms.

I wanted to go back to that place, so I could experience it after that trip as well. In the midst of that trip, there was so much going on internally that I wasn’t not sure I would be able to pull in all the details to convey it to a reader in the way that I wanted to. That was really about, as Gar says, spending time and immersing yourself in a way not just to have the experience, but realize your responsibility of sharing that space with the reader and making that place a player in the narrative as well.

For me, the challenge was this is a place that I love. The wilderness and Alaska is a place that I love, it’s beautiful, important, and wild; yet the story is terrifying. It’s sort of everybody’s worst nightmare, whether they’ve been in the wilderness or not. I didn’t want them to come away from the book with simply a terror of bears. I don’t think that would be responsible as a writer.

It’s not how I feel. It’s not how I think most Alaskans feel. We have the respect for it, but I needed to be able to balance the character of the wilderness. It was both terrifying and dangerous, but also beautiful, forgiving, and life-giving. That’s what I come away with at the end and that’s how I tried to follow the theme of the Requiem. At the end of the day, that Arctic wilderness that took away the most important part of my life at that point, gave me back this deeper understanding, in this profound way.

What is an Author’s Role in Representing the Wilderness?

Scott: What do you see as your role as an author representing the wilderness this way? I know that’s a huge question, but is there a part that you feel really called to sort of promote or make happen?

Gar: I think Shannon used a word I think must be an underpinning for all of it. that’s the whole issue of respect, for that within which we live. And everything that we’re given. The nature of humankind is to try to face challenges and endure or supervene and control it. I think nature has an indifference to all of that. Irrespective of what’s been portrayed in a lot of the post-apocalyptic works out there, I won’t call it literature, but popular films and that sort of thing, I think that the earth is much bigger than our worst fears from that standpoint.

Gar: My work is using the nature and the environment as a backdrop and as a testing point. Where I’m trying to go with my writing is an emergence of our conscience, consciousness, and ethics, so to speak. I think it defies human nature in many respects. It’s – I’m going to get Freudian here – but it is the superego enlightening us in terms of our responsibility as it relates to the respect that we should have for our overall environment. As well as for each other.

I use – just as Shannon said earlier on – nature has a “foil”, so to speak. As another character that brings out the best or worst in us. And as a way of reflecting on that which is internal to each of us. Your turn, Shannon.

Shannon: I think that’s great. You know, I’m not a connoisseur, I read one of the Hunger Games books just because I wanted to see what all the fuss was about, but that’s it. And I’ve put off reading The Road, by Cormac Macarthy which I imagine will be excellent, but, in a way that genre doesn’t appeal to me. In another way, I wonder if there’s some similarity in that it erases all of those distractions and allows you to really focus on the elemental aspects of our human experience. I know it’s doing much more than that, both the dystopian as well as a wilderness. But I wonder if there is some similarity in that? I don’t know for sure.

I will say that both the experience that precipitated the writing of North of Hope as well as the research that went into, which was in part research and in part experience, leads me to believe that I think the wilderness – like a sacred text, like a relationship – I think requires that you go deep into it. It requires of you that you continue to search it and not just easily dismiss it. In faith traditions, some of them will believe – there’s a quote, I think Dante – that “Nature is the second book of God,” or something. I think there is an aspect of wilderness that requires you to say, “Hey, this thing happened. I have to go into it. I have to go into that fear, into that experience, in order to be the person that I’m meant to be, in order to live into that experience in the way I’m meant to do.

Again, the wilderness just shaves away anything that’s extraneous, anything that might interfere. Because it requires going deep and because the more you learn, and really the research for North of Hope, I was trying to learn everything I could about the Arctic, much of which of course doesn’t end up in the book. And the more you learn, like any kind of learning really, I mean, learning about music or chess, or flying, now you know, whatever your choice of subject is. But there’s just endless layers to explore.

The wilderness really provides these phenomenal metaphors, maybe more than most anything else, right?

Gar: Yes.

Shannon: As with an iceberg, most of the plant life in the Arctic is below the surface, and you realize that is really what you’re asked to do, is probe below the surface. To find what’s beautiful, find how this environment works, how we’re a part of that environment. I totally agree Gar, it doesn’t care about us; it’s indifferent to us. Yet, we’re a part of it and there’s a real beauty in that. I think sharing and trying to explicate in a way that might be meaningful to somebody else is part of the responsibility. I took an extra step and continue to do so on some degree with activism on behalf of that environment.

I don’t think a lot of people have had the experiences where they’ve been forced to go deep. Allowing an experience where, for Gar, his characters can be tested and go deep, or for me, the narrator, myself, is tested and goes deep, sharing that with people in a way that says, “Hey this is worth our respect and our work to protect,” and whatever that means to each person. In a way, what I feel as a responsibility, as a writer. Although that’s not the purpose the story. That’s part of the responsibility of the writing itself, I believe.

Gar: Well, your story is a celebration. It’s a profound celebration.

Shannon: Thank you. I’m grateful for that interpretation. That’s what it’s meant to be. Absolutely.

The Leadership of the Author

Gar: Shifting a little bit away from the wilderness Shannon, you mentioned you’re working on leadership. I’m presuming then that you’ll be teaching it, writing about it, or conducting seminars?

Shannon: Right.

Gar: What are you planning to do with that?

Shannon: My real love is writing, and that’s what I continue to do most of the time. I’m working on two different manuscripts right now as well as several other projects. With the number of projects that are lined up, there are two manuscripts that are very different types of writing, but are related subjects.

The first is a leadership book and I am basing it on both my own experience as one of the first women to fly Apaches and about leading two platoons and a flight company, and serving in several other staff positions around the world. I’ve been interviewing women over the past year and a half who have been in similar roles over many generations, so that includes World War II WASPs, women who were even earlier aviators than I was before combat aviation was opened. Like combat aviators, some female general officers, and all of the different ranks. A submariner, a Coast Guard rescue swimmer. All these different women who have experiences similar to mine and yet very unique to their own experience. My goal is to try and pull out those similarities. The leadership book is taking all of these interviews as well as research in the area and putting them together. I’m excited about it. The blog has been called “The Grit Project.” I continue to do profiles as they come up, but I haven’t tried to keep up with a weekly schedule anymore since I’m working on the actual manuscript itself.

The second part is a manuscript I’ve been working on for a very long time, which in a way is more difficult and more complicated for me to write than North of Hope. This is looking at my eight years in uniform. That’s much more creative nonfiction, not the leadership type of book but a much more personal narrative. It’s incredibly complicated, in part because the experience is complicated and complex. A mix of pride and frustration and I’m pulling in artistic representations of the military to show this increasing complexity of the experience.

I’m really enjoying both of those projects. My livelihood, which supports the writing, is corporate and organizational presentations, keynote presentations. My signature presentation is called “Leading from Any Seat: Stories from the Cockpit.” I am very grateful that audiences seem to respond really well. I usually present a few times a month around the country. I think the leadership lessons, the good and the bad ones you learn from the military, are proved to be relevant in just about any environment.

That’s been a lot of fun. A little bit of a shift. I will always come back to the natural world; it’ll be part of my personal narrative for sure, not the leadership book of course. And then the poetry that I’m working on is tightly tied to that. The natural world will always be there, but I feel like I had to go into this part of my life. I needed to spend some time with it and come up with what it meant, really. That is what I’m doing right now.

Gar: That’s really neat.

Shannon: You’ve done a lot of leadership talking and speaking and training, isn’t that right?

Gar: Yes.

Shannon: You can give me some tips.

Gar: When we set up, the company I co-founded had a huge challenge in that we were bringing together a series of warlords who had their own groups similar to the size of the one I founded here in the Northwest. In 2001 they asked me to be the chief medical officer for the national organization, and we had 1,000 hospitals with them, 1,000 medical directors. Some of them were natural leaders and some of them were told “Hey you, you’re now the boss!”

In medical school they’ll spend very little time or give very little practical information in terms of how to survive in your lifetime, and how to indicate appropriately to other human beings, let alone people you have to lead.

One of the challenges that we had was to train the medical directors in leadership and in management. They’re two separate things in some respects. Management speaks to being able to conduct business and to do it with consistency, whereas leadership takes on the responsibility of going beyond a title and creating something that I call “resonant leadership.”

We taught our medical directors how to read others and to be able to learn their language, and then speak to them in their language… not speaking the medical director’s language, but the way that the person whom you are communicating with, whether it be a patient or the people that you were supposed to be leading, expected to be spoken to. And we showed the medical directors disparate styles of leadership, and used film clips from Attenborough’s Mother Theresa and Coppola’s Godfather to demonstrate different leadership styles and philosophies…what I’d call “coercive” leadership, and “reward” leadership, and comparing that to “title” leadership, and “resonant” leadership.

And I asked our directors to aspire to resonant leadership. To become someone with values and actions that followers can identify with. The “currency” that’s thereby created – by developing a persona around that behavior – is far greater than the currency you get from putting a gun to someone’s head, or giving them a dollar.

By being consistent in your values, the currency created outlasts other.

But I’m very interested, Shannon in what you’re doing, and I commend you for doing it. I think there’s powerful leadership inside of every one of us.

Shannon: What I love about what you’re saying, Gar – and I also love that we share this, because it’s not common – is that leadership is a creative act. It is an art. There is creativity in that. I think the talk I give on leadership storytelling addresses some of the issues you’ve talked about.

My favorite clip to show in that presentation is from Gettysburg. When Chamberlain’s talking to the deserters of the 20th Main. And then I have a JFK clip. But, regardless, I think that communication, and the ability to reach people, is the same thing in leadership and writing. Obviously, you do it in different ways. You’re reaching them in different ways, but it is about communicating and relationship, isn’t it? It’s been very fun for me.

Initially, I felt like I was selling out. I was in the corporate world for a while and then, I came out, and I was just writing. But, at some point, you have to support your writing, as well. I thought, “Well, maybe I’m selling out, going back into this.” But I love business, and I love leadership. I’m passionate about what is good about it. I think I learned a lot of lessons the hard way, and some, the right way.

Being able to combine the creative effort with those with an interest in getting things done and motivating people. The relationship piece of it is a real blessing, to be able to continue to let that part of life be nurtured as well. I love hearing you describe that as relationship and communication. It really does that relate to that, as well.

PART 3: Fiction, Poetry, & Learning Grit From the Wilderness

Fiction and Poetry

Gar: Shannon, are you tying that into your next work, in some form, in fiction work? Are you going do any fiction, or will it all be nonfiction, from that standpoint?

Shannon: My desire is to move into fiction. I have a novel I started, years ago, I’ve played with on and off. I have several short stories, one that just came out in The Road Ahead, as part of a veteran’s fiction anthology, and some other work I haven’t submitted for publication, that are short stories.

But it’s interesting, because things I feel like I’m most drawn to writing right now continues to be creative nonfiction. Not necessarily a memoir. After this memoir, I must say, I get a little tired of delving deep into oneself. I like to delve deep into a character. That might be a more fun project.

I don’t know for sure what the next big project will be. I have a way to go. I mean, I’m ready to submit them back to an agent this year. They’ll obviously have the cycle that manuscripts go through. In the meantime, I’m enjoying some poetry. I’d like to finish a few more essays. I think I’ll constantly play between fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. I’m finding the subjects come to me in the form they seem to want to be represented in.

The poems I write will come to me as poems. They don’t start out as essays or short stories. And short stories come to me as short stories. They don’t come to me as an essay that I try to rearrange. Interestingly, based on some feedback from my brand-new writing group, which I’m very excited about. I may try to write part of the current memoir as an exercise, as a piece of fiction, and give my narrator a different name or even make them a different character, just to get into it a little closer. With memoirs, sometimes the challenge is letting people in enough, I think.

I need to do better at that. I guess the answer to your question is that I’ll continue to play in all of those fields. I do aspire to end up where you are in the fiction realm more solidly.

Gar: You talk about poetry. Scott, you’re a poet.

Scott: Well, I’ll break my facilitator character here. I would call myself a working poet. I do instant typewriter poetry. A couple years ago, I gave myself a mission to write and give away 1,000 poems in a year. The act of doing that transformed my life.

I have this great 1946 Smith-Corona typewriter my grandfather used, when he was a traveling salesman for one of the precursors to Xerox machines. It got passed down through the storytellers in our family, and now, I have it. I’ve been using it for 20 years to make ‘zines, and stuff like that.

A few years ago, I started writing and working on my mission. Not writing just about myself, because it’s kind of like you’re saying with memoir. At some point, I’ve only got so many loops going on in my head I’m like, “Oh. Well, what about?” And, “what would you like a poem about?” I sort of found myself writing poems based on one word, or story inspirations by other people. I found that I was good at it, and I could write in the moment and open that channel. So, after doing 1,000 poems a year – in order to write that many, I had to interact with a lot of people – I couldn’t think about things too hard. I had to just write in the moment. And I found that I loved it more than I ever thought.

Now, I’ve started to do that as part of what I do day-to-day, from anything from weddings, corporate events to private birthday parties. And it’s a lot of fun. people really like it. It’s a new dimension of poetry that’s opening.

Shannon: You know, I met my first typewriter poet at the Seattle Center last year, with my two little boys. And it was a complete– I just didn’t even know what to expect. She was sitting there, and she said, “What do you want a poem about?”

I said, “Little boys.” I mean, I don’t know, two little boys were walking back to the car. And it is brilliant! It’s beautiful. I don’t know, it’s eight lines. It’s really beautiful. I’m going to frame it in pictures or something for my husband, for Father’s Day. Hopefully, he doesn’t hear this. I’m just blown away. I mean, it’s, so, good for you. I feel like that would be an outstanding creative exercise. I’m tempted to try it, but I’m not sure. I wouldn’t be as good as you in this!

Scott: Oh, do it. I did it at stage improv for a year while I was doing that 1,000-poem journey. I’m terrible in improv shows. But I loved it — the practice. Especially because I’m prone to just thinking too much. Or just going over and over things.

When you write a poem, or anything, when you write something, that’s the way you do it. You write it down, and you can really get stuck in the over-judging or editing phases of it. I still do that with some poetry. But the thing I really like about instant typewriter poetry is, when that woman wrote it for you – or when I write for other people – you have those three minutes, whatever it is. You just learn to trust what comes. Like you say, it comes to you in a particular form. It really is a practice. It’s unlike anything else I’ve ever done, in just letting it be, and building around. There’s no mistakes. You just build around what comes. It’s a very different type of writing. You end up with a very different, inspired piece of art.

Shannon: Wonderful.

. . .

Scott: I’m interested to hear about your poetry, and that … please.

Shannon: Oh, well, I think, in a way, it’s a little random. It’s not random because I tend to use a prompt. Again, I’m not challenging myself to go out right now and go write a poem, necessarily. Usually, when I do that, I fall flat on my face. That’s where I fear I may not do very well at the typewriter poetry! Usually, I feel like it comes to me in something I usually see is outside.

I recently wrote a poem, that I just read last night at the National Poetry Month reading, along with several others, about a short video that I can’t un-see. This is about a father in Aleppo pushing back the hand that is holding the plastic sheet that’s covering his son, who has been killed. It’s about being over here and being powerless. I think it’s the sense of powerlessness and overwhelm.

Lots of things come up, though, writing in the desert. I realize, it’s actually a family issue that I’m writing about – that may or may not or bubble up. I don’t know if I have a description for … they don’t cohere at the moment, I’ll say that. I’m also finding that as I try to organize my desk, I have them all, tucked into these little journals. I really need to get them in one place, so I can revise, and see if there is any coherence in any of them.

There’s one I played with a little bit, that was based on my second pregnancy. The medical world had advanced in the three years between my first and second son, and the blood test are taken on day one of pregnancy now and they can tell the sex of the baby. Which we didn’t wanna know. But they can tell everything about the baby.

And it turns out that there’s this, I’m gonna get this wrong, but it’s a … Gar, you’ll know the name, probably, but, micro-something. Any pregnancy a woman ever has, the cells from that baby or the fetus – whether or not it lives – are in her body for the rest of her life.

And that’s pretty powerful. I mean, that’s incredibly powerful.

They’re doing all kinds of studies around this, and trying to find out what they can learn from it. I think, in some cases, they find that those cells protect the mother, against certain illnesses, which is also incredibly powerful. But in other cases, they might also attack some of the mother cells. So, it’s just an interesting scientific fact that seems to lend itself to a lot of metaphor.

Looking for those specifics that seem to be directly metaphorical are fun to play with. As a mother, I think they’re fun. I’ve tried to write poems about my kids or about family. And that doesn’t, my immediate family, that doesn’t seem to come as naturally yet. So, we’ll see.

I do feel like the material presents itself in the form it wants to be presented. Which is just an interesting experience to now write in the different genres, and to feel that…

I’m a little disturbed to find that, even some that are lovely, natural world poems, there’s some darkness in this stuff. I don’t know! It’s not entirely comfortable. But that’s what comes out, so …

Gar: That’s the value of ambiguity, as you know.

Shannon: Right.

Gar: Looking into the definitions, the multiple definitions of a word, and the juxtaposition of them all.

Shannon: Yes.

Gar: You just gave me an insight, as you were talking about the antibodies that a mother will form, will be formed in a mother’s womb as a result of whatever pregnancy one had – including miscarriages. An antibody, antibody’s, effectively created around our, all of our experiences…

Shannon: Yes. Yes, absolutely. See, that does not need to be part of the story, somehow. I think it’s microchimerism. I don’t know how that it’s pronounced, but I love that, Gar. There’s all those layers of metaphors. And then, the more you know about just, the medical facts in that case, or natural world facts, in the case of plant life in the Arctic. The more you go into the knowledge of the specific, the more it’s revealed. I think that’s powerful in writing, in most forms.

Gar: Yeah, you talked about something else to do, Shannon, about the musicality. It’s tied into your work, and then, correlation with, and relationship you had with the requiem. I wondered whether other people would be able to read into that. I learned a term in theater, from a pretty erudite theater professor, who made us carefully study every one of the characters. If we did Shakespeare, he would come with tomes of research he’d done. Even minor characters in the Shakespearean plays, or whatever we happened to be doing at the time.

Even if I’d play a bit part I would have a book’s worth of literary allusions to the character – complete with pictures that he’d ripped from journals – and a number of other things. He used to call those things he gave to the cast “the secrets” which belonged to the ensemble…secrets kept away from the audience…that made it the production special.

We carried them with us on stage, and whether or not we were able to convey any of those secrets to the audience was irrelevant. We had those secrets ourselves.

So, when you were describing words of hope, and the correlation to the music, I thought, “Those are joyous secrets, aren’t they? Those are wonderful.”

Rereading your book will allow one to scratch down a little bit, and kick down past some of the ambiguities into other layers, under the tundra, so to speak, or wherever you were.

Shannon: Yes. Yes, I think that’s right. That’s the fun part of any kind of creative process, I think. Or really getting into that. Absolutely.

Learning Grit From the Wilderness

Scott: We’ve touched on a lot of different topics here today. A fascinating discussion. You both said a little bit about the projects you’re already working on. Just so everybody knows, we’ll put links to them and existing works in the post underneath this video.

As we close, I’m fascinated by what I see as a theme of the wilderness in literature, leadership, and the various things both of you are talking about, which is that idea of grit, to touch on your current project, Shannon.

If you could share something you’ve learned about “grit”, or something you think is important to the wilderness experience in writing. It takes a lot of grit to write one book, let alone several, like you’ve done. If there’s anything you would like to leave us with about that topic, let’s close with that. Gar, would you go first? And then, we’ll have Shannon close us out.

Gar: Sure. I can only speak to the durable character that I’ve got in my saga, so to speak. It moves through, probably 50 years in her life, with her family, in the backdrop of an emerging consciousness about human rights. Not only a woman’s place in the world, but all the other non-enfranchised groups. The character we created is a durable character. She’s not a kick ass heroine, the way that Shannon is in her real life, but I think Emmy could probably have learned how to fly a helicopter, had they been available.

The mettle that is her backbone, for me, is what is necessary to endure. Not only, environment, but also, the vicissitudes and prejudices that existed all throughout society at that time. What that metal is melded from is the consistent application of equanimity, in the context of always doing the right thing, and irrespective of what the person has been confronted with. Whether it be individual sociopathic behavior, or that type of sociopathic behavior that is unleashed during a time of war.

That’s the grit there. It’s grit, by necessity. She doesn’t even know she has it, until she’s confronted with the other loss of her family. Then, it all comes out. I don’t look at Emmy as a woman. I look at her as a mensch, as somebody who does the right thing. That’s who my character is.

Shannon: Fantastic. That’s great.

Scott: Shannon?

Shannon: I think grit is part of any character. Finding that, or potentially failing on the way, and then, ultimately, reconnecting to grit is part of any good narrative. From the leadership perspective, Angela Duckworth, of course, has made this very popular in her Leadership Lab, and her Character Lab, at University of Pennsylvania, but she defines grit as passion and perseverance towards a long-term goal.

I always ask the women I profile, how they would define grit. I get lots of different definitions. I came up with a definition early on, that it was a dogged determination in the face of difficult circumstances. Which is not very lyrical, but I think, in a way, it’s appropriate, because it’s not lyrical.

When I think about my tendency to say there’s no similarity between the manuscript of the book North of Hope, and the manuscript I’m working on, in some regards there are. Because at the end of the day, when you have circumstances, or a wilderness setting, or a dystopian setting that really puts our character to the test, and pares it down to the essentials of humanity and the human experience.

The human experience in the world is where you find your grit. Whether you’re looking for it, or you are forced into it by circumstance, I believe it’s something we all have. In leadership terms, I try to say, “This is at the intersection between your purpose and your passion.” We talk a lot about purpose. I think it’s something we all have, and is part of the human condition, if we are put in the right circumstances and we’re ready to receive it.

Art is looking for grit in many regards. It’s looking for those core elements of who we are and what our experience in this consciousness is.

Scott: I’ve kept you both longer than expected. I really appreciate this, and it has been really awesome for me to hear. Both of you explore the wilderness, and all the different things that comes out of that.

Thank you, Gar, and thank you, Shannon, both very much for making the time. And I hope to talk to you both soon.

Shannon: Thank you, Scott. Thank you, Gar, so much. Take care.

Gar: All right. Thank you both. Goodbye.